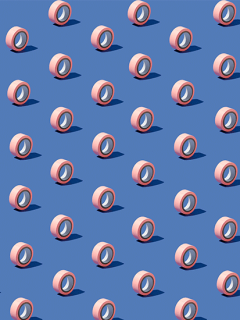

With the online tool for personalised adhesive tapes, many customers have already designed their packaging tape themselves and added their company logo, address, homepage and other texts. Behind the scenes there is a lot of technology and know-how, especially from the printing sector. Since certain specifications, e.g. on image quality and file formats, should be adhered to for a perfect result, we would like to inform you about the technical aspects of printing on adhesive tape.

But don’t worry if all this is too complicated for you: our customer advisors can always help you with your wishes. We also have professionals for the design who will make sure that your adhesive tape looks the way you want it to!

Flexographic printing – The printing process

Flexographic printing is a letterpress printing process. This means that the areas to be printed are raised on the printing form (the cliché), i.e. they are higher. This principle is familiar from everyday life, e.g. potato printing or stamps. Since it is a direct printing process, the printing forme is pressed directly onto the printing stock, just as with a stamp. Accordingly, the motifs must be laid out mirror-inverted when making the cliché (see picture).

As a customer, of course, nothing has to be mirror-imaged. This is done during cliché production. In fact, the name flexo printing also refers to the printing plate (the cliché). In contrast to Gutenberg’s cumbersome lead typesetting, the printing plates are made of flexible plastic and then applied to a printing cylinder.

A separate cliché is made by the printer for each colour of your design, so the more colours you want to print the more “dies” are needed. These one-off production costs for the clichés must therefore be added to the purchase price, but are usually waived once a certain quantity has been purchased.

The ink is transferred to the raised (printing) surfaces of the cliché in the printing process and applied to the printing material (your adhesive tape) in the next step.

The “substrate” in this case is your personalised adhesive tape.

Positive printing and negative printing

Two important technical terms on the subject of printing on adhesive tape are positive and negative printing. These refer to the design of the layout and the associated implementation in a stamp. Let’s assume your motif is a simple circle. In positive printing, this circle remains raised on the stamp and the rest of the area is removed. The circle shape then touches the substrate later during printing and applies the ink. The booking stamp from above is a classic example of positive printing.

With negative printing, on the other hand, the circle is “cut out” or removed from the stamp. The remaining area remains raised and touches the adhesive tape during printing. Thus, the background around the circle is printed in colour and the circle itself is left blank. Depending on the colour of the adhesive tape, this then shines through in the form of a circle.

In the following example you can see the difference once again:

In positive printing, the original ribbon colour forms the background and the print motif the foreground.

In negative printing, the white colour of the ribbon shines through. The blue background colour was printed on and the lettering was left out.

As a little mnemonic for “negative printing”: If you do not want your tape to have the typical tape colour (brown, transparent, white), then you must print your desired colour as the background.

The printing colours

Colour theory is a science in itself. The human eye can distinguish (according to calculations and estimates) about 20 million colours. It is a great challenge to use this enormous variety of possible colours:

RGB: Your screen mixes colours “additively”.

The colours of digital images on televisions, smartphones and computer screens are created by light. The three primary colours red, green and blue (hence the term “RGB colour”) are played out as tiny, separate dots of colour of varying brightness. In the eye, these are then “mixed” to produce a correspondingly coloured area. If you look at your screen from a very short distance, you may be able to see the different colour dots. When enlarged, it looks like the picture.

By adding the colours in a suitable brightness, the eye gets the impression of white. Without light, i.e. without luminous colour dots, the impression is of black or dark. The image on your screen becomes sharper the more tiny “colour dots” it can display. In private, you may have noticed this when switching from a tube TV to an HD set.

CMYK: Your office printer mixes colours “subtractively”.

While your monitor basically “does nothing” (no light) when displaying black colour, your printer has to go to great lengths. Here, the perception of black is created by superimposing all three colour components cyan (bluish), magenta (reddish) and yellow. White, on the other hand, cannot be represented or printed in this way, but is usually the basic colour of the printed paper.

However, this black (as can also be seen in the picture) is not completely dark or “deep black”. Therefore, most printers have another cartridge in the colour black, also called “key”. This enables the printing of deep black and gives colour images the necessary depth that cannot be created by mixing the other colours alone. In the picture you can see the different colour applications of an image, separated according to the original colours.

Not only your office printer, but also professional printers usually work with CMYK colours and therefore demand print data with CMYK colour profile. So under the magnifying glass, a printed image is a huge collection of tiny colour dots of the colours C, M, Y and K in different sizes, which (as on the screen) are mixed by your eye and perceived as a large whole.

Printing with a cliché: spot colours

When printing your adhesive tape, the flexographic printing process is used, as already mentioned. Here the basic colours are not fixed, but you yourself determine “in which colour pot” the stamp will be dipped to perfectly represent your logo. You can choose from an almost unlimited range of colours. For example, you can use the Pantone colour system, which currently includes almost 1,800 colours (HKS and RAL are also possible).

The purpose of these colour systems is to create an internationally uniform and binding standard. This means that colour determination is not based on eyeball measurement and you can be sure that the green you order will also be the green you print. You can find an overview (without claiming completeness) of the colour systems on these web pages:

- Pantone C: http://rgb.to/pantone/coated/page/1

- HKS: http://www.visual-graphics.de/de/service/hks-farbtabelle

- RAL: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAL-Farbe#Farbtabelle

For a 2-colour print, 2 printing clichés (stamps) are produced. In 2 steps, these are then each dipped into 1 colour pot from the selection above and pressed onto your adhesive tape.

Vector graphics and pixel graphics

In the Rajaprint tool, you can easily incorporate graphics, such as your logo, into your design. In order to achieve a perfect print result, it is important to differentiate between the types of images and the corresponding file formats. We therefore explain the difference between pixel graphics (raster graphics) and vector graphics.

The pixel graphic

In everyday life, we are most familiar with the term pixel in the field of digital photography. For example, the camera of the current iPhone (11) has 12 megapixels. This means that the camera records around 12 million different pixels (and their colour) in a photo. These are then displayed in an area 3264 pixels wide and 2448 pixels high, resulting in the image. Each of these 12 million pixels is defined with its position in the area and the colour of the pixel. A picture of our company building in Ettlingen serves as an example. It was taken by a professional photographer in a size of 5760 x 3840 pixels (this is also called “resolution”). Thus, it is very detailed and the file is correspondingly large. For the view in our blog it was reduced to 800 x 533 pixels. If you zoom in closer, you can already see the individual pixels.

You can quickly recognise a pixel graphic by its file format: the most common are .bmp, . gif, . jpg/.jpeg, . png and .tif (click here for a complete list of file formats).

The size of the resolution is extremely important for the quality of the print. The unit DPI (dots per inch) is decisive for this. On the screen, graphics can be enlarged and reduced at will, but if an image is to be printed, it has a real, fixed size that we can then view, e.g. 5 x 5 cm. Dots per inch relates this real size to the available pixel data in the image file.

As an example: For printed products (e.g. flyers) the requirement is usually 300 dpi, so that the image result gives a sharp and high-quality impression when viewed. For a printed image that is 5 x 5 cm in size, this results in the following minimum pixel size:

- Conversion cm to inch: 5 cm / 2,54 = 1,96 inch

- Conversion inch to pixel: 1.96 inch x 300 pixel per inch = 590.6 pixel

The image file must therefore have a resolution of 591 x 591 pixels if it is to be printed in the size 5 x 5 cm. In the following picture you can see the result on the “A” of the RAJA logo, if a graphic contains too few pixel information for a certain size.

How do you find out what resolution your image is?

With the free programme IrfanView (download at: https://www.irfanview.com/) you can check what size and resolution your graphic has. Via the menu bar Image -> Information you get an overview of the relevant image data.

The vector graphic

Vector graphics have a decisive advantage over pixel graphics: they are “lossless scalable” and thus independent of the number of pixels.

The vector graphic

This makes it possible to scale a graphic, e.g. a logo, to any size, regardless of whether it is to be printed on a business card, a poster or a jumbo jet. Since a logo is supposed to do just that, logos are also usually created as vector graphics and then saved as pixel graphics, as needed. One disadvantage is that they can usually only be created and edited with a professional graphics programme. A free alternative is the open source programme inkscape (download at: https://inkscape.org/de/).

You can quickly recognise a vector graphic by its file format: the most common are .eps, .svg, . cdr (from the software Corel Draw), .ai (from the software Adobe Illustrator) and possibly also .pdf files(here you will find a complete list of file formats). The formats printed in bold are optimal.

Vector graphics are optimal for creating printed adhesive tapes. If you have your logo / graphic as a vector format, you should definitely use it to configure your adhesive tape. If an advertising agency has created your logo, you can definitely ask them for the corresponding file.

Otherwise, you can of course contact our experts. They will advise you on the creation of your adhesive tape and will always find a solution.